Soap Making Heat Transfer Method

I’ve found that riding momentum is a good way to get shit done. This philosophy might stem from my natural laziness, but laziness aside, you can’t deny that it’s effective. The soap making heat transfer method is a great way to ride momentum. Let me explain.

Lye + water = hot lye solution. The solid fats in your soap recipe need to be melted (requires heat). You’re going to mix your lye solution with your fats anyway. It only makes sense to use the lye solution’s heat (momentum) to melt your solid fats.

Is this a perfect method? No. If you’re recipe is full of solid fats – too much to be melted by the heat of your lye solution – then this isn’t going to work for you. Luckily, most of us don’t have too many solid fats in our recipe to make this work.

Another itty-bitty downside to this method is that you have to work quickly after mixing your lye solution. There’s no leisurely prep time to weigh oils (or maybe even weigh oils + wonder off to eat a brownie and tell yourself it’ll serve as soapmaking “fuel”) while your lye cools down. You need to ride while the momentum is still there. As soon as your lye is thoroughly mixed into your water, you need to mix it into your solid fats. You know what that means, right? You’ll have needed to weigh out your solid fats prior to even daring to dump your lye into water or it’s all over and you’re back at your stove heating up shea butter and coconut oil.

This little bit of planning ahead is worth it, in my opinion.

Here’s how it goes:

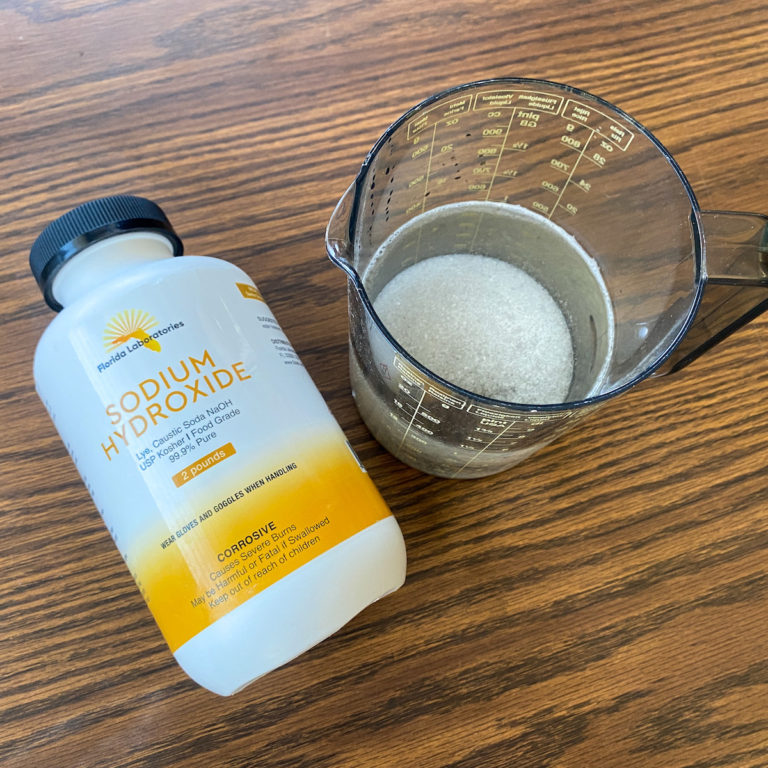

- Weigh out at least your solid fats, lye, and distilled water. Ensure your solid fats are in a lye safe container. Remember that smaller chunks will melt faster than big fat blobs, so break up your fats with a spoon or whatever tool you damn well feel like breaking fats with. NOTE: While you have your scale out, if you want to weigh out all the other stuff you’ll be using too, that’s an A+ for you. Mise en place.

- Prepare your lye solution as usual. For me, I find it’s impossible to know the exact moment when the lye is thoroughly mixed into the water, so I just mix the solution around longer than I think I need to, to increase the chances of all the lye dissolving

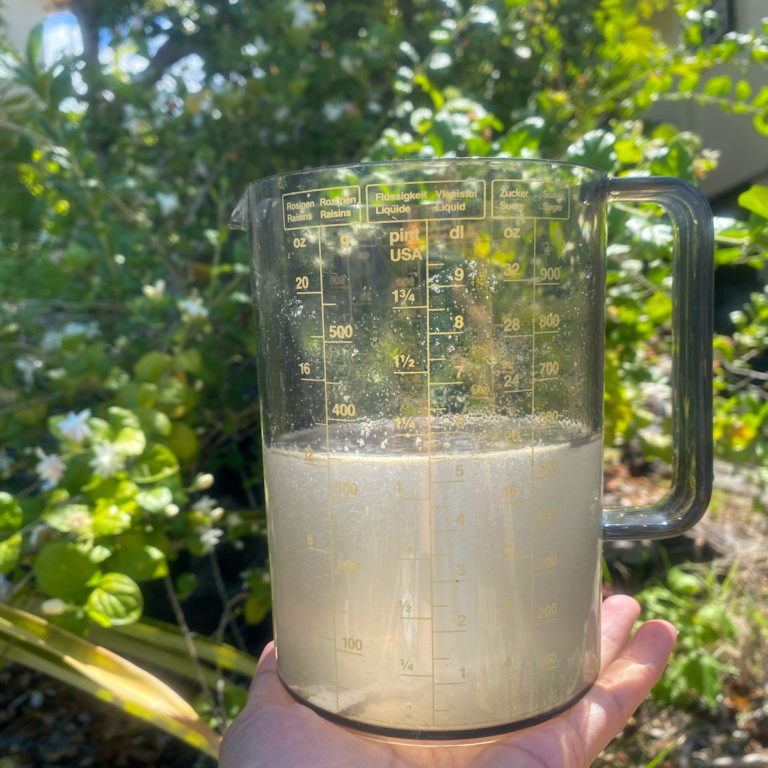

- Carefully pour your lye solution into the container holding your solid fats.

- Mix with a spoon or spatula (no hand-blenders yet) until all the fats are melted.

- Mix in your liquid oils, bust out the hand-blender if you use one, and make soap!

I like using a temperature gun when doing this. My solid fats always seem to melt slower than I expect it to. I don’t know why I always expect speed. You think I would maybe draw on my past observations and accept that it’s not an instant process, but I find myself thinking “hurry up and melt, hurrrrry” every time. But that’s beside the point. I was saying I like using a temperature gun when using the soap making heat transfer method, and that’s because I can assure myself at various points in time as I impatiently wait for fats to melt, that yes, the lye solution is still hot enough to melt my fats.

Here are the melting points of common soapmaking oils. If your lye solution is above these temperatures, trust that it’s working to melt your fats, and just help it along by stirring.

- Coconut oil: 76°F / 24°C (some coconut oils have a 92°F / 33.333°C melting point if it’s been hydrogenated to make it more solid)

- Cocoa Butter: 93-101°F / 34–38°C

- Shea Butter: 89-100°F / 31-38°C

- Tallow: 90–95°F / 32–35°C

Everytime I’ve bothered to check the temperature of my lye solution upon mixing, it well exceeds 200° F, yet as you expected, adding fats to it will reduce the temperature (unless your fats are hot, which doesn’t apply to what we’re doing here).

By the time the fats are melted down from the heat of the lye solution, my batter usually drops to around 99 – 113 ° F. I add in my liquid oils, which drops the temperature lower, and then the temperature raises again during blending.

Overall the soap making heat transfer method gets a big thumbs up from me, and its how I personally make the vast majority of my soap.