Do I Have To Let My Lye Solution Cool Before Using it?

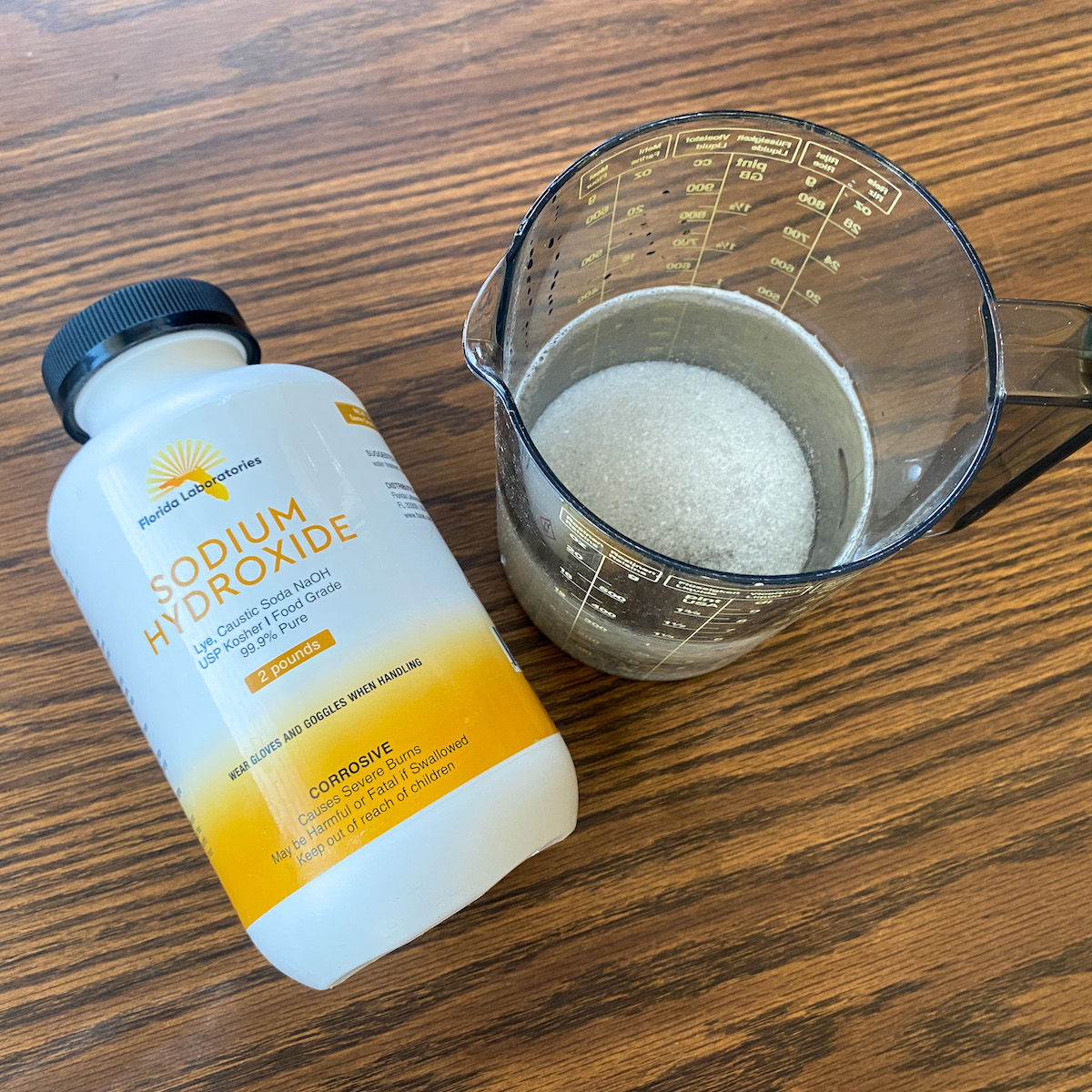

Of all the materials a soapmaker works with, lye is the most dangerous. A highly caustic chemical that seems to serve as the catalyst to some really strong reactions, it must be treated with care.

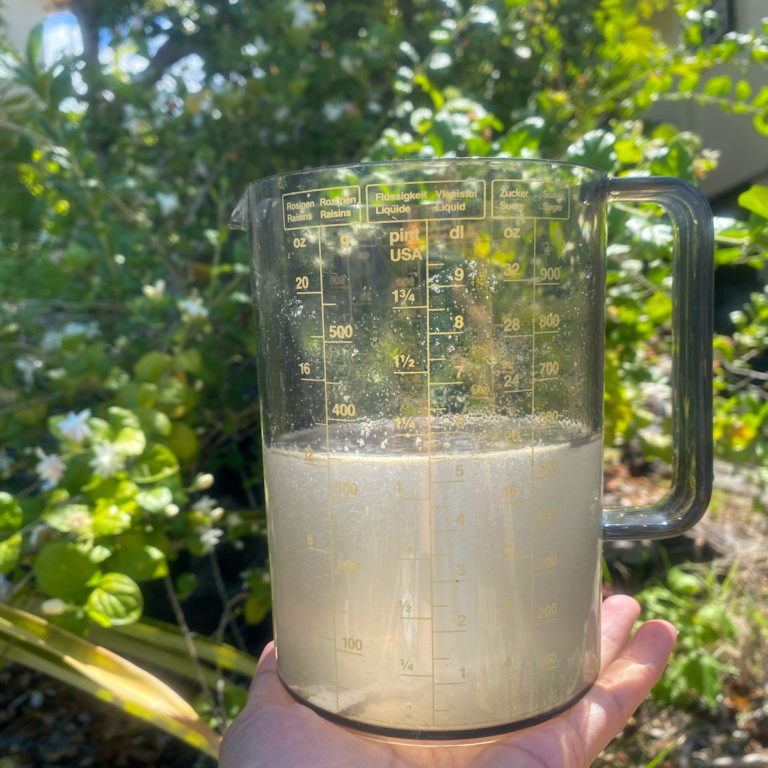

Each and every time you make lye solution, you’re causing an exothermic reaction between the lye and water, which is why it gets so hot and creates fumes.

As you may already know by now, when making your lye water, you should always add your lye to your water, not the other way around. Adding lye into your water will cause a volcano effect (the lye dissolving into water will start to form a crust that the rapidly heating lye solution below it will violently burst through) and ain’t nobody got time for that.

So you add your lye into your water carefully and slowly, then what? You wait until it cools? If so, do you wait until it cools all the way down to room temperature? Or do you use it when its a certain temperature? Or can you save yourself the wait time and use it while it’s hot?

Really, any of these are fine as far as safety is concerned, so you just want to go with the method that gives you the results you’re looking for.

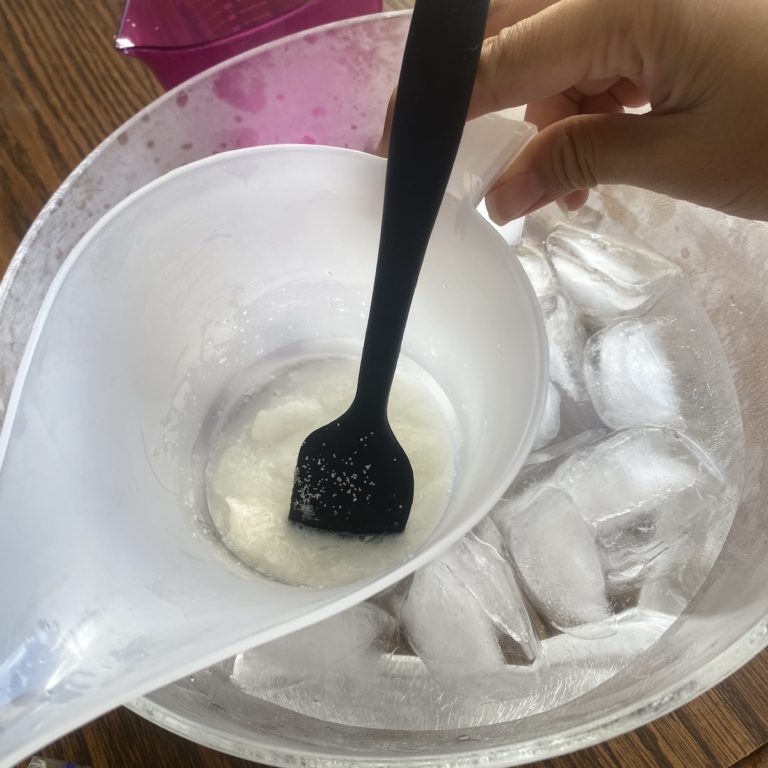

Some soapers choose to mix their lye solution into their oils at room temperature. You gently heat your solid fats until they’re just melted (or in the summertime you may find that your normally solid oils are already melted), add your liquid oils to it (which will reduce the temperature), then add your room temperature lye solution to it (which will further reduce the temperature) and mix away. This is a nice simple method of soapmaking that works especially well with masterbatched lye solution.

Many soapers advise mixing your oils and lye solution when they’re between 100-120 degrees, and/or within 10 degrees of each other. Keeping track of temperatures to this level of detail is most likely to yield the most consistent results, so this is what I would advise if that’s really important to you. This temperature range should ensure that your solid fats are thoroughly melted and there’s no cool lye solution to potentially speed the solidification of those hard oils, so it can remain liquid and therefore be properly saponified.

But you don’t actually have to wait until the lye solution is cooled down to begin soaping. Some take advantage of the extremely hot temperatures of the lye solution (sometimes upwards of 200 degrees), pouring it directly onto hard oils so the heat from the lye solution melts the hard oils. This is called the heat transfer method, and can be done if you have a reasonable about of hard oils in your recipe. If you’re trying to make a soap made completely out of butters and coconut oil, for example, the heat from your lye solution would most likely not be enough to melt all the hard oils that need to be melted.

If you try the heat transfer method and find that it works for your recipe, know that you can’t just bank on using this same process when scaling the recipe up. You have to see if it still works when you have a larger amount of hard oils that need to be melted.

Some really experienced soap makers also choose to add hot lye solution to hot oils for countertop hot process soap making. This can cause some really extreme reactions to the batter like volcano-ing, so do not try this unless you’re highly experienced and ready to handle a hot bubbling mess that wants to crawl out of your pot.

Letting your lye solution cool is a matter of personal preference, but at least some level of cooling is recommended unless you consider yourself a true pro and prepare like one too.